Notre Dame event models the hospitality needed for national healing

This article originally appeared at Baptist News Global on December 11, 2024.

As I walked through the snow toward McKenna Hall at Notre Dame University, I imagined the next 12 hours would include hard truths and valuable insights from professors and pundits about the reelection of Donald Trump and the Republican takeover of Congress.

The 2024 Election Postmortem was hosted by Notre Dame’s Center for Philosophy of Religion. It sought to answer three main questions: What happened, what to watch for in the days ahead, as well as planning, partnerships and practical steps for the next four years.

Notre Dame’s Center for Philosophy of Religion focuses on bringing philosophy and theology into a conversation to provide insights for every day, normal people.

“If there’s any issue where we might expect Notre Dame would have a voice that we hope the rest of the country and the world would listen to, it’s on the question of faith and religion and how it relates to democracy,” said David Campbell, professor of American Democracy and director of the Notre Dame Democracy Initiative.

And to be sure, the next 12 hours did not disappoint. The event, which was envisioned and organized by Kristin Du Mez, brought together a unique blend of professionals exploring three well-balanced themes that combined honesty and hope. But perhaps the most meaningful expression of Notre Dame’s voice at this event was its hospitality.

Reaching out

One of my earliest memories in life was watching a Notre Dame football game at my grandparents’ house in 1987. The reason I remember this game so clearly is that I yelled, “I hate Catholics!” And suddenly, my dad was informing me that my aunt, who was in the room, was a Catholic.

Of course, I had no idea what Catholics were. But my independent Baptist parents were recent graduates of Bob Jones University, which is a fundamentalist evangelical university whose founder called the pope the Antichrist. So I imagine my hateful outburst toward Catholics was learned at home.

Up until 2015, I was a fully committed evangelical Christian nationalist who never would have imagined sitting under the teaching of a Catholic. So in a sense, this conference felt like a group of people having a conversation about how to reach out to my past self.

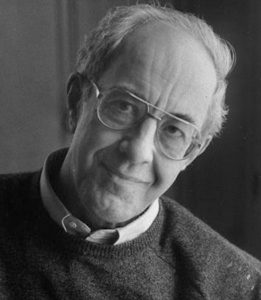

My journey of walking away from Christian nationalism and opening toward my neighbor began with a spiritually healing journey of self-awareness that fostered a love of neighbor as self. The first seeds of this journey were planted when I was required to read a book called Reaching Out, by Henri Nouwen, who taught at Notre Dame in the 1960s. And for me, experiencing the 2024 Election Postmortem felt like the embodiment of Nouwen’s reflections on hospitality.

Hospitality in an academic setting

In evangelical spaces of gender binaries, hospitality is typically considered the work of women, while men provide the entirely different discipline of teaching. But in Nouwen’s theology, hospitality is about more than setting out donuts and coffee. It is about postures within, toward and among one another. And for Nouwen, hospitality is crucial for academics.

Nouwen defined hospitality as “the creation of a free and friendly space where we can reach out to strangers and invite them to become our friends.” As I told Kristin Du Mez after the event, it felt like being with old friends despite so many of us never having met.

Much of this was due to who Du Mez and Notre Dame brought together for the event. As Nouwen writes, the affirmation of one another provided in hospitality “often means just bringing the right persons together or setting apart time and place where more thinking can be done.” That’s exactly what the 2024 Election Postmortem provided.

I mentioned to Robert P. Jones between sessions that it’s interesting how many of these events are being hosted by academics, and yet they’re connecting with people who aren’t academics. Jones said given what the academics are noticing in their research, they’re realizing conversations need to be had and these events are how they know to have them.

But despite having the knowledge about data the rest of us don’t have, the academics Du Mez has been gathering aren’t driven by hierarchy, but rather by hospitality. As Nouwen suggests, “Teachers who can detach themselves from their need to impress and control, and who can allow themselves to become receptive for the news that their students carry with them, will find that it is in receptivity that gifts become visible.” He suggests a teacher can be “a receiver who can help the students to distinguish carefully between the wheat and the weeds in their own lives and to show the beauty of the gifts they are carrying with them.”

At the 2024 Election Postmortem, the professors and pundits on the three panels not only shared their insights but invited the insights of the guests. For one thing, even something as subtle as referring to us as “guests” was a way of fostering a feeling of having a table conversation. Also, our questions and insights during the discussions were clearly valued, as if we were offering a gift to the hosts as well. And as Nouwen points out, when that happens, “the distinction between host and guest proves to be artificial and evaporates in the recognition of the new found unity.”

A unity of diverse backgrounds and perspectives

One of the most beautiful moments of the conference for me was a conversation I had around a table with a half dozen of the panelists and guests. Three of the women had no church background, one of the men was a pastor, another was a Notre Dame professor, and two of us came from conservative evangelical backgrounds.

We talked about how our different families approached the holidays during our childhoods and how our current experience of Christmas is affected by the wonders and wounds of our childhoods. We shared stories of hell houses, altar calls, yoga and carefully designed Bronze Age figurines gifted by a hippy mom. We laughed and lamented through the complexity of it all.

None of us tried to convert the other to our theology or politics. We were simply present together in the stillness of stories. And although most of us around the table wouldn’t be interested in attending the institutional church the professor or the pastor led, we were together in what Nouwen would call a “friendly emptiness where strangers can enter and discover themselves as created free; free to sing their own songs, speak their own languages, dance their own dances; free also to leave and follow their own vocations.”

Why? Because, “Hospitality is not a subtle invitation to adopt the lifestyle of the host, but the gift of a chance for the guest to find his own.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!