Ten things I learned as a religion writer in 2022

As 2022 draws to a close, I wanted to reflect back on what I’ve learned this year as a religion writer.

The vast majority of my articles are published by Baptist News Global, which is a reader-supported, independent news organization that covers “the people, events and ideas that are shaping American religion and culture.” They are looking to cultivate “change-making conversations about Christianity and culture among Baptists and other inquisitive people of faith.” And they do so “from a perspective that is Baptist in heritage and ecumenical in spirit.”

Even though I am not currently a Baptist, I share their Baptist heritage because I grew up as an independent Baptist and spent most of my adult life in conservative evangelical churches that functioned like most mainstream Southern Baptist churches do. Today, I’m personally more of an ecumenical spirit. So BNG has been an excellent fit for me to explore and analyze the theological, ethical and political conversations shaping our world today.

Even though I am not currently a Baptist, I share their Baptist heritage because I grew up as an independent Baptist and spent most of my adult life in conservative evangelical churches that functioned like most mainstream Southern Baptist churches do. Today, I’m personally more of an ecumenical spirit. So BNG has been an excellent fit for me to explore and analyze the theological, ethical and political conversations shaping our world today.

BNG published 37 of my articles this year, totaling over 91,000 words. The majority of my articles are analysis pieces that provide a more in depth theological analysis of the conversations and events that happened throughout the year. And by the end of the year, I ended up having five of the top ten most-read analysis pieces for BNG.

For many religion writers, writing is about telling people what to believe and how to behave. This is not the approach I take. Instead, as I see it, writing is about learning, loving and liberating. It provides opportunities to grow in self and neighbor awareness. By working through the historical, theological, psychological, social, linguistic, political, and relational narratives with an attentiveness to self and neighbor awareness, we can be moved to love ourselves and our neighbors. And as love does its work of cultivating centered compassion, it liberates us from the power dynamics that dehumanize and exile us.

In no particular order, here are 10 things that I learned from writing about religion in 2022.

1. Exploring the bizarre and the strange are opportunities to plunge the depths and reaches of our fears.

Sometimes a piece catches the attention of readers because the story it tells is almost too strange to believe. The year started off with a story about how the board of Bob Jones University called a fashion student’s wrap coat “blasphemous.” Another story was a response to Owen Strachan’s tweet against men having long hair. And a third exploration of the bizarre and strange detailed the plans of a doomsday vault full of servers and cassette tapes meant to preserve fundamentalist sermons in the event of an apocalyptic attack by the LGBTQ community on conservative churches who post their sermons online.

Sometimes a piece catches the attention of readers because the story it tells is almost too strange to believe. The year started off with a story about how the board of Bob Jones University called a fashion student’s wrap coat “blasphemous.” Another story was a response to Owen Strachan’s tweet against men having long hair. And a third exploration of the bizarre and strange detailed the plans of a doomsday vault full of servers and cassette tapes meant to preserve fundamentalist sermons in the event of an apocalyptic attack by the LGBTQ community on conservative churches who post their sermons online.

While each of these articles felt like watching a patriarchal train wreck, they also provided opportunities to explore how deeply our fears hide and how extensive they reach.

- How a student’s fashion design project upset the created order at Bob Jones University

- This is a tale of testicles, fertility, the length of men’s hair, and one bizarre tweet

- Doomsday Vault created to preserve conservative preaching against cancel culture

2. Naming the abuses of powerful men are opportunities to free people from their grip.

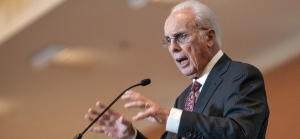

John MacArthur speaks to a large group of Southern Baptists June 12 in Anaheim, Calif. (BP photo)

The pieces that lead to the most “hate mail” from angry readers are articles that expose the preachers or politicians that they look up to. The men that I dealt with this year were Voddie Baucham, John MacArthur, Trent Hunter, Albert Mohler and Matt Chandler.

Each of them have supporters who believe that my writing is worthless and that I will one day spend eternity burning in hell for the things I wrote about their theological heroes. These articles led to responses ranging from church members within their ministries to seminary professors and presidents.

But while wrath was poured out by some who look up to them, thankfulness was expressed in private by others. Part of the liberation process is helping people who are still in these ministries to realize what’s going on, while another part is reminding those who have left why they made the right decision.

- Plagiarism is the least thing to worry about with Voddie Baucham, who is a threat to children, women and daughters

- What has John MacArthur actually said about race, slavery and the Curse of Ham?

- Desiring God is denying reality

- Should adultery and homosexuality be illegal? Mohler weighs in

- What have we learned about Matt Chandler’s sin and restoration? Not much

3. Learning from history gives context for the power dynamics of our present.

One of the most impactful trends in religious writing recently has been the contributions from historians such as Kristin Du Mez and Beth Allison Barr. Their knowledge of history shows us how culture has shaped our identities, impacted our theology, and formed the power dynamics that exile us from self and neighbor.

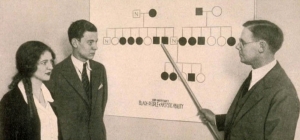

Eugenicist Paul Popenoe counseling a couple on hereditary preservation, 1930. (Eugenics Archive)

While I am by no means a historian, I wanted to spend more time this year learning how our present situation has evolved from our past, as well as discovering events of the past that we may be reliving today.

Some of the topics I explored were the history of “biblical family values,” worship songs during the Civil War, Christian Zionism, spanking in public schools, and the U.S. Constitution. I also contrasted how we tend to assume history is written from the historiography that the biblical authors were providing.

- There’s a straight line from eugenics to ‘biblical family values’ to white supremacy and the anti-abortion movement

- Learning from the political worship songs of our American past

- How Trump’s latest comments on Israel align with evangelical Zionism

- Schools and spanking: Isn’t it time we stopped using religion to justify violence?

- No, Dan Patrick, God did not write the U.S. Constitution

- The biblical view from the Tower of Babel

4. Attending conferences online are great opportunities for learning from a variety of communities.

The articles that took the most work by far were of the three conferences that I attended. Conferences are great opportunities to learn because they are organized with a variety of speakers that a particular community values and include a well planned theme that reflects the way they see reality.

The first conference that I attended this year included the perspectives of conservative to moderate evangelicals that were open to calling out racial discrimination, but were non-affirming of LGBTQ people. The second conference was organized by atheists who were dealing with the religious trauma that many evangelicals experience. Then the final conference I attended was a more progressive Christian conference that fully embraced a faith that is Christian and yet that evolves. Each of these conferences brought some perspectives that the others did not. And they all had radically different views of reality. So learning from all of them provided a holistic learning experience that simply attending one of them would not have provided for me.

The first conference that I attended this year included the perspectives of conservative to moderate evangelicals that were open to calling out racial discrimination, but were non-affirming of LGBTQ people. The second conference was organized by atheists who were dealing with the religious trauma that many evangelicals experience. Then the final conference I attended was a more progressive Christian conference that fully embraced a faith that is Christian and yet that evolves. Each of these conferences brought some perspectives that the others did not. And they all had radically different views of reality. So learning from all of them provided a holistic learning experience that simply attending one of them would not have provided for me.

Many conferences now provide online access to their events. So for each of these conferences, I was able to access all of their sessions, transcribe many of their conversations, and provide the most detailed review that I am aware of.

- Exiles in Babylon conference gets so much right but can’t apply its logic about race to sexuality

- What I learned listening to others who have left the faith

- On Halloween, thoughts about passing from darkness into light

5. Systematic theology can make total sense while fueling senselessness.

Systematic theology is a way that Christians attempt to organize their beliefs about God and reality in a logical, organized framework. It tends to value consistency throughout the framework. So truth often gets filtered through how it fits within the system. As a result, every idea within the framework makes total sense to those who hold it.

Because the framework and the ideas within make total logical sense, its followers may not recognize how senseless their framework actually is. And so, a denial of reality and a sacralization of abuse can grow without the people living out those dynamics ever realizing what they’re doing.

Because the framework and the ideas within make total logical sense, its followers may not recognize how senseless their framework actually is. And so, a denial of reality and a sacralization of abuse can grow without the people living out those dynamics ever realizing what they’re doing.

This year, I explored how systematic theology can make total sense while fueling senselessness in issues of inerrancy, abortion, parenting, and complementarianism.

- How the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy became a litmus test

- The tangled web of evangelical opposition to abortion while believing in original sin, eternal conscious torment and the mysterious age of accountability

- White evangelicals want to control you so their kids can live forever

- What does complementarianism have to do with Domestic Violence Awareness Month?

6. Technology provides opportunities either to exile us from one another or to foster communal wholeness.

When Covid shutdowns began in 2020, we became acutely aware of how technology connects us. But as conspiracies spread online, it also became clear how technology drove many of us apart.

As we began coming out of isolation and gathering together, many of us had different opinions on how to bridge the journey from connecting through technology to connecting in person again.

But I wanted to explore technology, not as an impediment to embodiment or an escape from reality, but as a new integrated part of reality that has the potential to foster communal wholeness.

But I wanted to explore technology, not as an impediment to embodiment or an escape from reality, but as a new integrated part of reality that has the potential to foster communal wholeness.

The technologies we discussed included live-streaming worship, talking with your kids about pornography, Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter, the James Webb Space Telescope, and Artificial Intelligence.

- A response to Tish Harrison Warren about livestreaming worship

- How to talk with your kids about porn without sending them straight to hell

- What will Twitter’s $44 billion purchase do to theological discourse?

- Why you don’t need to play a drinking game to understand the wonder of the James Webb Space Telescope’s first images

- How The Jetsons and Westworld help us think about robots, personhood and faith

7. Conversing with those who differ from you can help you learn to love more fully.

Especially in religious spaces, we can tend to live in an echo chamber, mostly reading and interacting with those who agree with us. But this year, I wanted to explore how differing voices can help us learn to love more fully.

Perhaps nobody is more misunderstood by Christians than transgender people. So in an article about the transgender national champion swimmer Lia Thomas, I sorted through the history of women’s sports, the current political laws about transgender athletes, and explored how we can find common humanity with transgender athletes.

Having led worship for two decades, one of the most formative people for me early on was Michael W. Smith with his worship albums and political songs. But as I grew older and deconstructed my conservative theology and Christian nationalism, I began to differ with Smith in a number of significant ways. One particular storyline that happened late in 2022 was when Amy Grant decided to host her niece’s same sex wedding. Franklin Graham immediately took to Twitter to disapprove. And Michael W. Smith, who is friends with both of them, was put in an awkward position. So I wrote a piece about how Grant and Smith’s friendship has the potential to help Smith move away from the Christian Zionism and nationalism he is caught in and move toward love.

Having led worship for two decades, one of the most formative people for me early on was Michael W. Smith with his worship albums and political songs. But as I grew older and deconstructed my conservative theology and Christian nationalism, I began to differ with Smith in a number of significant ways. One particular storyline that happened late in 2022 was when Amy Grant decided to host her niece’s same sex wedding. Franklin Graham immediately took to Twitter to disapprove. And Michael W. Smith, who is friends with both of them, was put in an awkward position. So I wrote a piece about how Grant and Smith’s friendship has the potential to help Smith move away from the Christian Zionism and nationalism he is caught in and move toward love.

In my final piece of the year, I opened back up toward conservatives by interacting with a conversation between Russell Moore and Mike Cosper of Christianity Today about their views on the theological conversations of 2022 and where they would like to see the discussions move toward in 2023.

- Here’s a better way to talk about Lia Thomas and transgender athletes

- Amy Grant will host a same-sex wedding, Franklin Graham objects, and where does that leave Michael W. Smith?

- Russell Moore and Mike Cosper almost get there: A conversation on theology and anger

8. Restorative justice is still the best news.

Evangelicalism claims to have the “good news.” One assumption that I began to form a few years ago was that for the “good news” to be good news, then it has to have some semblance of goodness in what it says and in how it accomplishes what it says it will do.

Many of the struggles today come down to how we see everything being made right. Conservative evangelicalism believes in retributive justice that makes things right through punishment. But restorative justice seeks to make things right through healing every wound and bringing every exile home.

Many of the struggles today come down to how we see everything being made right. Conservative evangelicalism believes in retributive justice that makes things right through punishment. But restorative justice seeks to make things right through healing every wound and bringing every exile home.

Thanks to data by sociologists, true crime dramas by Netflix, and insights from mystics across religions, I was reminded throughout the year why restorative justice is still the best news.

- New data show America’s challenge is not because ‘both sides are wrong’

- Our obsession with true crime dramas and what ‘Dahmer’ teaches us about heaven and hell

- On meeting death as a sister

9. Worship lyrics have the power to dehumanize or liberate without our consciousness realizing what’s happening.

The most powerful moments of connection for Christians is often in times of worship together. The collective effervescence of music, technology, and friends converging together to sing about what Christians value most provides an experience that is mostly unparalleled throughout the week.

Because the focus is on the glory of a God most high, they often don’t recognize the identify forming hierarchies that are built into worship lyrics. Most of these power dynamics are not even noticed by the songwriters themselves. But they most definitely are there and are shaping the way evangelicals view themselves in relationship to one another.

Because the focus is on the glory of a God most high, they often don’t recognize the identify forming hierarchies that are built into worship lyrics. Most of these power dynamics are not even noticed by the songwriters themselves. But they most definitely are there and are shaping the way evangelicals view themselves in relationship to one another.

This year, I explored how these dynamics play out in the song “Above All,” as well as in the worship songs that were written by Black and white communities during the Civil War. And then for Thanksgiving, I reflected on three stories from Jesus about how gratitude can allow hierarchies to slip past our defenses without us knowing.

- How Michael W. Smith, George W. Bush and one popular worship song expose the problem of Calvinist theology and politics

- Learning from the political worship songs of our American past

- Three stories from Jesus about the danger of hierarchy and gratitude

10. We are all evolving.

It can be quite frustrating for many us when we continue to see family and friends posting the things they do on social media. One of my personal struggles is when I see their inconsistencies. They’ll praise their children, despite what their theology says about their children. They’ll talk about all things being made new, despite the fact that their theology says very little will be made new.

While the inconsistencies should be pointed out, it’s also important from another perspective to be okay to some degree with inconsistencies. Those are the places where growth can occur. In fact, none of us are perfectly consistent.

While the inconsistencies should be pointed out, it’s also important from another perspective to be okay to some degree with inconsistencies. Those are the places where growth can occur. In fact, none of us are perfectly consistent.

One of the exercises that helps me is to look back at my own journey of evolving. So I shared three autobiographical pieces this year about my church journey from the Baptist world to the Anglican world and beyond, about how we evolved our educational journey from private school to homeschool to public school, and about how I process theology these days.

By recognizing how I’ve evolved, I can learn to approach myself with courage, compassion and patience in my continued journey of evolving. And when I see myself from that place, I can begin to see my evangelical neighbors in the same way, meeting them where they are, but all the while doing what I can to confront the power dynamics within American religion in order to foster learning, loving, and liberating.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!