BioLogos Integrate helps us make all things new while beginning where we’re at

This piece was paid for by BioLogos Integrate. However, the opinions expressed within are my own and include my thoughts about the strengths and weaknesses of the curriculum.

At the heart of Christian theology is the story of a God who meets humanity where we are at by entering into our world, wearing our skin, learning our languages, and growing as a human. As the Franciscan friar Richard Rohr says, “God loves things by becoming them.”

N. T. Wright

Inherent to this theology of incarnation is the idea that God is concerned about our engagement with the earth. New Testament Scholar N.T. Wright says: “Heaven and earth are designed to overlap and interlock.” He believes that in the future, a time will come when “they will do so fully and for ever, as the New Jerusalem comes down from heaven to earth.” According to Wright, “The point is that the Spirit is given so that through the work of the church the kingdom may indeed come on earth as in heaven.”

If the work of the church is to manifest the new creation of the kingdom of God here on the earth, then it would seem important for the church to begin by learning about how God has decided to do the work of the first creation on the earth.

Of course, there are many different Christian approaches to talking about the relationship between science and faith. And many of these conversations tend to leave Christians divided, in exile from one another. But in Re-Enchanting the Earth, Ilia Delio says, “The roots of this breakdown can be traced to a complex of factors including … religious otherworldliness.”

The difficulty that many Christians face in integrating science and faith is that ever since we discovered in the fifteenth century that the earth was not the center of the universe, we have felt de-centered. With the growing acceptance of evolution and deep time over the past century, the disconnection has widened to where many modern Christians mistrust modern scientific consensus, which can lead to a dismissal of what we know about this world, or to hoping for an escape to another world.

But what if there was an opportunity for Christians to begin exploring this world and asking how they might relate their Christian faith to what they learn in science class? What if Christian’s aren’t relegated to exile from one another, from non-Christian neighbors and from learning about the universe they believe God created and incarnated into?

Francis Collins and The BioLogos Foundation

Francis Collins

As he shares in his book The Language of God, Francis Collins began thinking about Christianity after he was a practicing doctor as a result of conversations he was having with some of his patients. The world-renown geneticist went on to lead the Human Genome Project, served as the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for over 12 years, and was awarded the Templeton Prize.

Concerned about how Christians struggle to reconcile modern scientific consensus with their religious beliefs, Collins began The BioLogos Foundation in 2007. BioLogos affirms evolutionary creation, in contrast to other Christian ministries that support intelligent design or young earth creationism. Collins resigned from BioLogos after President Obama asked him to serve in the NIH. And BioLogos has been led since 2013 by astronomer Deborah Haarsma.

Science curriculum for Christian high school biology students

There are a variety of options for high school students in Christian families to learn about science. Some of the most popular curriculums, especially among homeschoolers and Christian schools, are from BJU Press, Abeka, and Apologia. But each of these options believe in young earth creationism, which teaches that the universe is somewhere between 6,000 to 10,000 years old, denies evolution as the story of human origins, and affirms a global flood.

One intelligent design alternative to these curriculums is Discovering Design, which accepts the concept of an older earth but rejects scientific consensus about evolution.

Another option is Novare Science, which takes a more neutral approach to evolution. It presents evolution as a theory without many of the mischaracterizations and theological warnings that other curriculums use. But it presents evolution as one legitimate theory among others, allowing for Christians to have a variety of views.

Given the affirmations and denials of the course options for Christian high school students, BioLogos saw an opportunity to create a curriculum that writes from an evolutionary creation perspective, while giving space for questions and gracious dialogue among those who are processing what they believe and why.

Collins explains: “We have to have a way for young people who are interested in science, whose faith is a rock on which they stand have the opportunity to see how those things do fit together. And now, there’s a way for that to happen.”

Katie Crews

Katie Crews, who teaches middle school science for the Trinity School of Durham and Chapel Hill, believes Integrate has accomplished just that. “I think Integrate really fills in a gap of solid scientific education from a Christian perspective,” she says. “And it definitely doesn’t dilute or dull down the Bible at all. Both of those things are brought in full force.”

However, the Integrate program is meant to be an option for Christians to use as a supplement to their secular science textbooks, rather than as a standalone curriculum. Faith Stults, the program manager of Integrate details: “We believe that secular science textbooks provide high quality science content. Christian educators have expressed that what they’re missing are curricular resources that address the intersection of science and faith. For this reason, we intend for Integrate to remain a supplementary curriculum. However, we see a lot of potential to expand it to include other science topics (ie. physical sciences) or equivalent elementary and middle school resources in the future.”

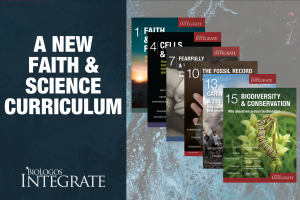

BioLogos Integrate: A Faith & Science Curriculum

Integrate is a supplemental science curriculum that brings faith and science into a dialogue guided by leading scholars in their fields. Even though it is designed for high school students, it can be easily adapted for sixth grade up to early undergraduate students.

The curriculum covers fifteen units, including such topics as:

- Ways of Knowing—How do we gain trustworthy knowledge in science and theology?

- Cells & Design—Does the complexity inside a cell point to God?

- Genetic Diversity & Human Dignity—How does understanding genetic differences illuminate the inherent worth of all people?

- DNA Technologies & Ethics—How should faith inform our acceptance of new technologies?

- Bible Interpretation & Science—What kind of answers can we expect from the Bible?

- The Fossil Record & Faith—Does the fossil record support the theory of evolution?

- Climate Change & Our Commission—Should Christians care about climate change?

Meet: Each unit begins with a video introduction from a specialist in the topic of study. The experts include an astronomer, conservation biologist, geneticist, paleontologist, urban farmer, climate scientist, biblical scholar, and others. Following the video, the student can engage with discussion questions about what was said in the video as well as about what will be covered in the unit.

Meet: Each unit begins with a video introduction from a specialist in the topic of study. The experts include an astronomer, conservation biologist, geneticist, paleontologist, urban farmer, climate scientist, biblical scholar, and others. Following the video, the student can engage with discussion questions about what was said in the video as well as about what will be covered in the unit.

Grow: The next section in each unit is a devotional overview of a Christian virtue along with Scriptures to read and questions to discuss. Included are such virtues as humility, joy, integrity, vulnerability, wonder, hope, and many others that are relevant to exploring faith and science.

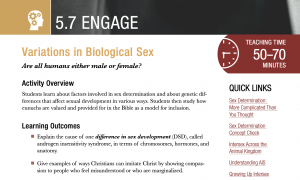

Engage: One of the interesting aspects of Integrate are the activities that explore a topic related to faith and science. Topics include unraveling the conflict thesis, different kinds of knowledge, what scientists are really like, variations in biological sex, the human enhancement continuum, Alzheimer’s and Dementia care, ancient cosmology and literary structure of Genesis 1, transitional fossils, miracles and science, a lament for extinct creatures, and more.

Experience: Integrate also offers hands-on science activities for each unit. Examples include activities related to the adaptive design of skin color, evaluating GMO’s, evidence for evolution, whale hunt, history in our genes, a restoration project, and backyard biodiversity.

Integrate: Each unit closes with an opportunity for the students to reflect on what they have learned. These reflections tend to have themes of people coming together and moving forward. They include recognizing your own gifts and abilities, moving toward people with differences, disagreeing well, moving forward in faith, making all things new, and applying our values to conservation.

Each unit is flexible enough so that the curriculum can be completed in any order. And while the lessons tie in to one another, they can be completed individually as well. They’re primarily grouped into four main topical bundles: Strong Foundations, Human Biology & the Big Questions, The Bible & Origins, and Creation Care.

Opening up to modern science through biblical scholarship

Having spent most of my life as a young earth creationist, I never thought I would one day come to embrace what scientific consensus says about the age of the universe and about biological evolution. Ironically, what led me to question my beliefs about science was not science, but the Bible.

From the Bible Project video “Overview: Genesis 1-11”

My young earth creationist pastor shared a Bible Project video about Genesis as a creative way of capturing our attention during his sermon. I was stunned by the way the biblical authors connected stories to one another through literary links. The more Bible Project videos I watched, the more fascinated I became with the Bible as a work of literary genius. But eventually I began to wonder: given the amount of literary interdependency within the Bible, how much of these stories literally happened?

The more I dug into the scholarship that Tim Mackie, Bible Project founder, and others recommended, the more I began to learn about the conversations that the biblical authors were having and how the cosmological assumptions of the ancient near east shaped the way they wrote.

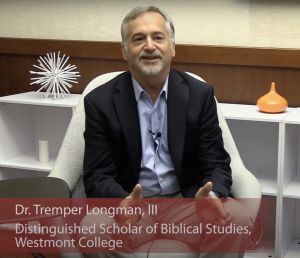

Tremper Longman

Integrate utilizes Bible Project videos, as well as teaching from biblical scholar Tremper Longman to explore how the ancient world of the Bible saw reality and how it can speak to people today.

“Who was the original audience? And what were they afraid of? What did they hope for? What questions did they ask?”, one of the unit videos asks. “Consider for example the story of creation in Genesis, the first book of the Bible. While a more modern audience might want or even expect a fact-based scientific explanation for how all things came to be, the original intended audience — the people of ancient Israel — were more concerned with how their God — Yahweh — compared with the gods of the neighboring Egyptians and the Babylonians.”

Once you begin to realize that the primary concerns of the biblical authors had to do with how Yahweh compared to other gods — rather than communicating a scientific narrative — and when you learn about the ancient literary devices that the biblical authors used to communicate these ideas, you can feel the freedom to explore what the experts have been learning about and confirming over decades of peer-reviewed research in both biblical scholarship and in science.

Trusting the experts

Growing up in young earth creationist Christian schools, I was very wary of evolutionists, especially Christian ones. I had a sense in which there was a conspiracy among scientists to keep Christians from being able to present their case for the scientific inerrancy of the Bible in academic settings. As a result, I didn’t trust scientists.

After the biblical scholarship of people like Tim Mackie, John Walton, Peter Enns and others freed me to consider the possibility that modern scientific consensus may be safe to consider, I began listening to the Unbelievable? Podcast, where atheists and agnostics dialogued with Christians from a variety of perspectives about science and faith.

The more I listened, the more I began to trust that the BioLogos affiliated scientists knew what they were talking about scientifically.

Through these podcast episodes, I began hearing about BioLogos, as well as hearing how their representatives handled both science and faith. The more I listened, the more I began to trust that the BioLogos affiliated scientists knew what they were talking about scientifically. And due to the way they talked about their Christian faith, I trusted that they weren’t part of a conspiracy against Christians. Because Francis Collins read and understood the data of the human genome, believed that evolution is true, and still remained a Christian, he seemed like an expert I could trust.

Probably the best feature of the Integrate curriculum to me is that it eases the concerns of Christians who are considering the possibility of believing in modern scientific consensus by utilizing the scholarship of theological and scientific experts and building trust through dialogue between the two fields.

Holding together the “Two Books”

BioLogos uses the metaphor of “God’s two books” when talking about “the idea that God reveals himself through both Scripture and nature.”

Integrate defines special revelation as “truth that is communicated supernaturally by God to believers.” It explores a variety of sources that Christians have considered to be special revelation, from those who believe it comes exclusively from Scripture to others who believe it can also come through “prophets, angels, dreams or visions, or the Holy Spirit.” It also mentions how some Christians believe the Bible to be direct revelation.

They define general revelation as “truth about God that is accessible to all humanity through reason, experience, conscience, or observation of the natural world.” This is where nature understood through science can be seen as a second revelatory book. So BioLogos refers to “God’s book of works (nature) and God’s book of words (the Bible),” or “God’s Word and God’s World.”

One point of emphasis that BioLogos focuses on is the lack of contradictions between the two. “What God reveals in one book must not conflict with what God reveals in the other book,” the curriculum says. “Apparent conflicts are the result of mistaken interpretations of one or both.”

Dealing with “apparent conflicts” between science and the Bible

When one book containing ancient cosmologies and metaphors is in conversation with another book containing deep time, biological evolution, and quantum physics, there are bound to be areas of disconnection for the reader.

Integrate illustrates two different approaches to these disconnections by having the students discuss the similarities and differences between how Richard Dawkins and Answers in Genesis approach science and faith. “Both see science and faith as fundamentally incompatible,” the curriculum notes, “either because faith threatens scientific inquiry, or because scientific inquiry threatens faith.” Instead, Integrate proposes that “the truth found in both faith and science can be harmonized and can work together to give us a better picture of reality. We don’t need to choose one or the other, and they aren’t in competition.” It also provides links to additional videos, podcasts and articles that help the student work through that harmonization.

Applying the “two books” and “apparent conflicts” to sex and sexuality

Perhaps the area of greatest concern for many Christians across the spectrum today is regarding how to approach human sexuality in light of what we read in the Bible and in science. Whether they are of a more progressive or conservative persuasion or somewhere along the spectrum in between, beliefs run deep and passions flow strong when it comes to issues related to human sexuality.

For the most part, I was pleasantly surprised to see how Integrate approached these issues. It begins by dealing with how sex is determined as well as how complex it may be. One of the most fascinating parts of the unit showed how sex in a variety of species is determined and at times changes during an individuals life through a variety of factors including genetics, the environment, or in some cases not even including a male sex at all. I especially appreciated how the unit specifically named and described how intersex animals and humans are created and included the story of an intersex person. One story the unit shared was of a village where “some individuals who appear to be biologically female at birth develop male genitalia at puberty.”

For the most part, I was pleasantly surprised to see how Integrate approached these issues. It begins by dealing with how sex is determined as well as how complex it may be. One of the most fascinating parts of the unit showed how sex in a variety of species is determined and at times changes during an individuals life through a variety of factors including genetics, the environment, or in some cases not even including a male sex at all. I especially appreciated how the unit specifically named and described how intersex animals and humans are created and included the story of an intersex person. One story the unit shared was of a village where “some individuals who appear to be biologically female at birth develop male genitalia at puberty.”

Because these scientific factors and stories open up questions for many who assume that sex and sexuality are rather simple, Integrate opens the opportunity for educators, parents and students to have dialogue about how their understanding of the Bible relates to the scientific complexities of human sex and sexuality.

With the “Grow” virtues that the curriculum promotes throughout the units, the desire would be for those in conversation to listen and speak with humility, joy, integrity, vulnerability, wonder, and hope. The unit on sex and sexuality specifically names compassion, asking: “How can we show the compassion of Christ to those who are different from us?”

When bringing these scientific complexities into conversation with Scripture, Integrate brings a number of passages to the table and asks such discussion questions as:

- What attitude does God show toward people who do not fit into the male/female binary in these passages?

- Jesus recognized that not everyone fit the male/female marriage pattern and God compassionately included eunuchs as part of his own family. How might this inform the way we include individuals with biological sex differences in our churches?

With the introduction to scientific data, the openness to dialogue, and the valuing of Scripture, Integrate seems to talk in a way that acknowledges complexity, encourages a pursuit of wisdom, but that Christians holding to traditional sexual ethics will ultimately approve of. “When we add topics like same-sex attraction, sexual behavior, and marriage to the mix, questions about how to apply biblical teachings can get very complicated,” the Extended Teacher’s Note on Sex, Gender, and Sexuality states. “It is wise to learn as much as we can, understand our convictions, and be as humble, loving, and empathetic as possible. We can work toward making our Christian communities more inclusive, welcoming, and compassionate without sacrificing our commitment to Christian sexual ethics.”

What is unclear is what is meant by “our commitment to Christian sexual ethics.” For conservatives, that could mean promoting an exclusive commitment to sex within a heterosexual monogamous marriage. But for progressives, Christian sexual ethics are about a more diverse and holistic Christian sexual ethic based on erotic attunement and values with curiosity, creativity, flexibility, and care for self and neighbor. BioLogos leaves the interpretation of Christian sexual ethics to the educators and students to discuss.

Restoration, cosmology, evolution and the future of Christian theology

“Finding a curriculum that’s written by scientists, educators, and theologians, putting all that together so that it’s good science, it’s good theology, and it’s good pedagogy. That’s magic,” says Peter Denton, who is the Head of School at the Trinity School of Durham and Chapel Hill.

Peter Denton

Integrate delivers on the convergence of theological and scientific experts teaching how science and theology can co-exist in a dialogue with one another.

But the one thing that stands out to me after reviewing the curriculum is how the present exiles in our minds and communities might converge toward unity. BioLogos desires to see the unity of diverse people around the unity of God’s two books. It seems that they see a telos of wholeness. In Scriptural terms, they refer to it as “making all things new.” BioLogos sees the vision of “all things new” as extending to the cosmos. To that end, I am in full agreement with the curriculum.

The question in my mind is where our current exiles are coming from. And my suggestion is that they are coming from the fractures of hierarchy and exile that come from ancient cosmology.

The Integrate unit on biblical interpretation states: “The Bible was written to a culture that had very different concepts about how the world was set up and how it worked. This is sometimes referred to as ancient cosmology or ancient cosmic geography. In the ANE, people had a different cosmic geography than we have in the modern scientific world.”

But “how it worked” in the ancient world included implications for human relationships.

But “how it worked” in the ancient world included implications for human relationships. Biblical scholar Kyle Greenwood explains in Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science: “The Mesopotamians thought of the upper heavens as a physical realm above the upper waters. Its floor was solid, enabling its residents to stand, sit, or otherwise conduct their affairs. Matters in the upper heavens paralleled matters on earth, such that when a king presented himself before the altar of Shamash in that god’s temple, it was as if he were standing before the throne of the god above the firmament.”

The cosmological hierarchy of the ancient near east continued to have an effect in shaping society in the Greco-Roman world of the New Testament. In Four Portraits, One Jesus, Mark Strauss explains: “Everyone knew their place in life—who was above them and who was below them. Democratic values of equality and equal rights were almost nonexistent. Though people certainly had ambition, the greatest goal in life was not to climb the socioeconomic ladder but to protect the status quo. This was done by serving those above you and exercising authority over those below.”

These cosmological-social hierarchies affected everything in the ancient world, including the way the New Testament describes salvation. In Tradition and Apocalypse: An Essay on the Future of Christian Belief, David Bentley Hart says, “In the New Testament … no concern could be more crucial to the understanding of redemption in Christ than a theology of the angelic archons and powers thronging the heavenly spheres above and separating this world from God’s highest heaven, or of the demons roving the earth, or of the kingdom of death below, or of the two ages of creation. … By his triumph over the cosmic archons, moreover, this savior has opened a pathway through the planetary spheres, the encompassing heavens, the armies of the air, and the potentates on high … . To the degree that any of this language persists in later dogmatic deposit, it has been attenuated to a miss of metaphor or displaced from the center of the picture and transformed into a kind of ornamental frame. Certainly the cosmology of the New Testament, along with its very troubling angelology, ceased to occupy any especially central place in Christianity’s official soteriologies within only a few generations.”

Sandy Richter

Ancient cosmology also had an affect on marriage and human sexuality. Biblical scholar Sandy Richter explains: “Marriage in the ancient world is very different from marriage in our world. Marriage was not the individual choice of two adults of legal age based on chemistry and compatibility. Marriage was an alliance between two families designed to distribute wealth in a mutually beneficial fashion. Even when chemistry was in the mix … economic advantage was still the controlling objective.” In other words, their top down patriarchal view of dominion and inheritance defined marital and family relationships.

Christians across the spectrum of beliefs about faith, science and their implications for marriage have a very different understanding of salvation and marriage than what was shaped by ancient hierarchical views of the cosmos. Regarding its implications for marriage, Richter says, “We find this foreign at best, offensive at worst.” But rather than continuing to enforce ancient patriarchy or throwing the Bible out altogether, Richter says that interpreting the Bible in these areas is a “cross cultural experiment.”

One concern I have about the Integrate curriculum is that while it recognizes the ancient three-tiered hierarchical cosmology of the Bible, it leans toward promoting the perception of a unity within the Bible and between the Bible and science that I would question. For example, regarding the “two books metaphor,” Integrate says, “What God reveals in one book must not conflict with what God reveals in the other book. Apparent conflicts are the result of mistaken interpretations of one or both.”

As I understand it, BioLogos sees no conflict between what is read in the Bible and what is read in nature. And throughout the curriculum, Integrate brings the two into dialogue including in such controversial topics as sexuality and climate change. The problem for me isn’t so much that there is a conflict between faith and science, but that there is a conflict between cosmologies. Ancient hierarchical cosmology created ancient hierarchical relationships. And it’s under the weight of hierarchy that people are crushed and that those who leave feel exiled.

The problem for me isn’t so much that there is a conflict between faith and science, but that there is a conflict between cosmologies.

While I agree with the concern that Integrate has regarding caring for the earth, they still frame it as a hierarchical exercise of dominion. They say that “a proper understanding of dominion over creation motivates stewardship, not exploitation.” In an article they provide, the author says, “Yes, God gave us dominion, but dominion should not be confused with license. Dominion implies great responsibility. We give teachers dominion over our children when we send them to school, but we would not be pleased if at the end of the day our children came home ignorant, battered, and bruised. The same principle applies to dominion over the earth; when God gave us dominion over the earth, he did not intend for us to destroy his creation. As God’s appointed stewards, we can use natural resources, but not abuse them.”

Despite the calls for stewardship rather than exploitation, the language of “dominion over” is still an ancient hierarchical metaphor that was used based on ancient hierarchical cosmologies. It is the same language that modern patriarchs use to justify their dominion over their wives as stewardship rather than exploitation. But I fundamentally disagree with patriarchy. So while I agree with the intention of BioLogos, I still would prefer that we evolve our language beyond the language of dominion altogether to a language of converging love that evolves us in complexity, depth and union as members of a cosmic family.

Ilia Delio

In her book, The Hours of the Universe, Ilia Delio explains: “We have not accepted evolution as our story. We treat evolution as a conversational theory or something that belongs to science, as if science is something separate from us and outside our range of experience. Politically, we have fiefdoms and kingdoms; socially, we have tribes and cults; religiously, we have hierarchy and patriarchy. There is nothing that sustains, supports, or nurtures human evolution.”

She continues: “By evolution, I mean simply that change is integral to life. We are becoming something that is not yet known. To live in evolution is to let go of structures that prevent convergence and deepening of consciousness and assume new structures that are consonant with creativity, inspiration, and development.”

For Delio, as well as for myself, “Theology is integrally related to cosmology.” So as our cosmology changes and our metaphors change to fit our new understanding of cosmology, so does our theology and our understanding of relationships within our theology and cosmology. We can see this demonstrated throughout church history as theology has evolved over time rather than remaining fixed and static.

As our cosmology changes and our metaphors change to fit our new understanding of cosmology, so does our theology and our understanding of relationships.

Showing how science and faith can co-exist is a vital first step that Integrate does an excellent job of providing for us. My desire would be that we evolve from there to examine how cosmology, theology, relationships and ethics are related, then observe the differences between how ancient cosmologies informed theology, relationships and ethics, and wonder what implications a change in cosmology may have for theology, relationships and ethics today.

Evolving in community: avoiding danger or provoking wonder

“One of the main reasons young people lose their faith when they go away to college is because of the difficulty in trying to put together these questions of faith that they have that science seems to contradict,” says author Phillip Yancey. “Often, churches are fearful of exposing kids to science because it might rattle their faith. Actually, it’s much more dangerous not to deal with these issues.”

The fear of the “danger” of young people losing their faith is what drives many of these conversations today. Young Earth Creationists and proponents of Intelligent Design are often concerned that learning about evolution will undermine the inerrancy of the Bible and the foundation for faith. Evolutionary Creationists are often concerned that faith will be seen as disproven in YEC and ID communities when the evidence for evolution is understood.

I understand why many Christians see the potential of their children losing faith as a danger. But I also have many atheist and agnostic friends who would see that fear as presumptively supremacist, as if somehow they are to be feared.

The reality is that we’re all part of the same human family no matter our views of faith or science. And we all have something valuable to offer to this conversation.

My preference would be that we move beyond language of avoiding the danger of losing faith that may cause our non-Christian friends to feel looked down on and that we would move toward language of provoking wonder at the cosmos we find ourselves in.

My preference would be that we move beyond language of avoiding the danger of losing faith that may cause our non-Christian friends to feel looked down on and that we would move toward language of provoking wonder at the cosmos we find ourselves in.

My desire would be that evolution isn’t simply one option in a conversation, but that it would eventually be seen as our story. When we finally accept that, it will have implications for how we interpret the nature of theology, relationships, ethics, and even the Bible itself when we realize how a change in cosmology leads to a change in language and metaphor.

But the reality is that we’re not there. We’re exiled into different ways of viewing the universe. And thankfully evolution doesn’t expect us to be somewhere that we’re not. Evolution happens right where we are, as a species adapts in community from where it’s at.

Thankfully evolution doesn’t expect us to be somewhere that we’re not. Evolution happens right where we are.

If I had a time machine, I couldn’t expect one of our common ancestors to relate to each other as modern humans do. Instead, God would have been patiently present with them in their community as they descended the trees and moved together out into the fields. And perhaps by knowing that story, I can rest in the idea of God being patiently present with us today in our becoming.

That’s what Integrate provides for the church today. It begins opening hearts toward one another so that we can trust that those we are conversing with are being transformed toward love as we are, and so that we can learn from the experts who are discovering how it all works. Integrate gives Christian high school students an opportunity to open up toward self, neighbor and God by learning about science with a faith that grows in complexity, depth, and union. Whether every student agrees with one another, or whether every reader agrees with my assessment of the curriculum is beside the point. The point is that this is where we’re at in our becoming. And Integrate is a much needed tool to help us begin to look more closely in community through this dark mirror we call the cosmos.

For those who are interested in purchasing Integrate, use the promo code RICK30 to receive 30% off your entire cart.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!