Learning from the political worship songs of our American past

This article originally appeared at Baptist News Global on November 16, 2022.

The American Civil War was “a war with a musical soundtrack,” according to Christian McWhirter.

And that soundtrack continues to echo through the American church today, illustrating the different life experiences of Black and white Christians in particular, once again “marching as to war,” as one popular hymn declares.

During the 19th century, music was everywhere. And while most history of the Civil War focuses on the details surrounding the conflict between the North and the South, very few have considered the role music played.

“Songs influenced the thoughts and feelings of civilians, soldiers and slaves — shaping how they viewed the war.”

“Although it was certainly a prominent part of Northern and Southern culture before 1861, the war catapulted music to a new level of cultural significance,” McWhirter writes in Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. “More than mere entertainment, it provided a valuable way for Americans to express their thoughts and feelings about the conflict. Conversely, songs influenced the thoughts and feelings of civilians, soldiers and slaves — shaping how they viewed the war.”

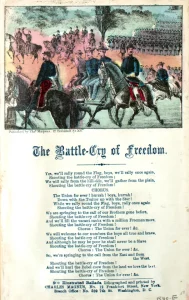

The primary role of music was “connecting disparate listeners and performers to the broader conflict,” according to McWhirter, a Lincoln historian. “Some pieces did this explicitly through lyrics directly referencing various aspects of the war, but others were more subtle. Patriotic songs taught Americans how to interpret the politics of the war, while sentimental ballads helped them cope with the spectrum of emotions a large and costly military struggle could introduce.

The primary role of music was “connecting disparate listeners and performers to the broader conflict,” according to McWhirter, a Lincoln historian. “Some pieces did this explicitly through lyrics directly referencing various aspects of the war, but others were more subtle. Patriotic songs taught Americans how to interpret the politics of the war, while sentimental ballads helped them cope with the spectrum of emotions a large and costly military struggle could introduce.

“Songs also allowed listeners and performers to understand their roles in a war-torn society. It was in the popular songs that Americans balanced their personal and civic responsibilities. Patriotic songs told them where their allegiances lay, but sentimental songs addressed how those allegiances could affect their personal lives.”

Between blackface and benefits

During the war, minstrels in blackface became popular in the North as a way of influencing how white people in the North perceived Black people in the South.

In the Music in Art journal, Melissa Zapata-Rodriguez says: “It was during the Civil War that minstrel iconography fueled even more the racial disparity that enabled white society in the North to fall into conflicting ideas about African Americans. Northern white society in the United States was comprised of abolitionists (radical and conservative), moderates and racists. These discerning views played an important part in music production during the Civil War, especially on the minstrel stage. Both racial animosity toward African Americans and abolitionists efforts in the North would mark the confusing, and somewhat contradictory sentiment that white Northerners would maintain during the American Civil War.”

In the South, Black people often were paraded around to sing and dance in order to “show how ‘happy they were,’” which McWhirter notes was “the favorite theme of Southerners.” Many of these events were benefit concerts that featured slave musicians in order to raise money for the war.

Between battlefields and wash bins

One month after the Civil War began, the United States War Department announced that each regiment would be allowed to have a 24-member brass band. Two months later, the Union army required every regiment to have two musicians.

“Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.”

In The Civil War 100, Michael Lanning says the North had 28,000 musicians who played in 618 bands, prompting Union general Philip Sheridan to say, “Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.” Robert E. Lee added, “I don’t think we could have an army without music.”

Even though music was key to everyone’s experience and processing of the Civil War, it evolved as the war developed. Songs toward the beginning of the war featured lyrics that emphasized recruiting soldiers to the cause. But as the armies filled their ranks, recruitment songs began to fade.

Even though music was key to everyone’s experience and processing of the Civil War, it evolved as the war developed. Songs toward the beginning of the war featured lyrics that emphasized recruiting soldiers to the cause. But as the armies filled their ranks, recruitment songs began to fade.

The most popular songs that emerged appealed to soldiers in battle. McWhirter says: “Pieces with melodies, lyrics and themes appealing to fighting men found the widest audiences. … In effect, soldiers became not only music’s most enthusiastic consumers but its most effective distributors.”

As the war came to a close, the bold singing of the Confederates began to waver.

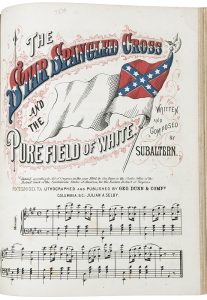

McWhirter says: “At the end of the war, Confederates experienced a crisis of confidence in their music — finding that the sting of defeat transformed many of their favorite anthems from bold statements of purpose to dour reminders of a cause lost.”

Songs in secret

But while soldiers on both sides of the war strode onto the battlefields with songs of purpose and triumph accompanied by professional musicians, the songs of the slaves were experienced in secret.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!